Engagement as Ecology of Learning

Posted on: May 12, 2022

Universal Design for Learning

by Mandala Barab

Universal Design for Learning is a philosophical stance and practical approach to planning, teaching and learning. UDL was initially inspired by the Universal Design movement in architecture and design. For the built environment, it turns out, it’s cheaper and more efficient to design buildings from the outset to be accessible for all people, including those with motion or visual impairments, for example, rather than needing to retrofit buildings with elements like ramps or elevators after the fact. Properly considered, it’s of course predictable that people with diverse abilities would need to enter and use any building, so we can see that Universal Design is truly a practical approach.

Similarly, in the Universal Design for Learning movement, we can break down that predictable variance into three vital dimensions: engagement, representation, and action & expression.. These dimensions represent the areas of probable variability in any class, at any age level, and by planning accordingly, we save time and increase the accessibility to content and skills for all learners. Put another way, by investing a bit more in our planning of lessons and units, we increase the ease with which students can actually engage with material during teaching. This is similar to the benefit in architecture of not needing to renovate a building after it’s built; for teachers that step is marked by the face-palm moment of realization that a lesson fell flat or a certain subset of students were locked out of learning - our ‘retrofitting’ often requires considerable differentiation, and when we realize the need to do so after the fact, we’ve lost valuable learning time that might have been saved by planning wisely. This is where we also run into the potential pitfall of self-fulfilling prophecies when teachers have different expectations for different students.

Engagement

Here, I want to do a deep dive into the dimension of Engagement. As a teacher new to UDL yet with many years' experience in the classroom, I’ve been surprised to find how poorly I actually understood engagement myself. It’s such a buzzy term, and yet, as educators, we often lack a shared understanding of what is meant by ‘engagement’, how to measure it, or how to grow it in our classrooms. I’m also going to take a counter-intuitive position that, in terms of engagement, what matters for teachers is different than what matters for researchers.

As part of my own exploration of engagement, I started with The Measurement of Student Engagement: A Comparative Analysis of Various Methods and Student Self-report Instruments by Jennifer A. Fredricks and Wendy McColskey. The researchers take us on a journey starting with how ambiguous the conceptualization of engagement often is, even in the world of educational research. They continue the discussion by outlining the challenges in measuring engagement, via multiple methods, from student self-reporting (surveys) to experience sampling, teacher ratings, interviews, and outsider observations. From there, the authors name behaviorial, emotional and cognitive engagement as key components of the construct of ‘engagement’. They conclude the paper with statistical methods for assessing the validity and reliability of various measures, and some of their own recommendations.

All of this is to say that I came away from this heavily researched study a bit shell-shocked to find that the discourse around engagement is in fact much wider, denser, and more convoluted than I had any reason to expect, and yet, again, I’m a long-time classroom teacher! I also stepped away at a loss for how this matters in my classroom. As a teacher, I don’t typically need to ‘measure’ engagement; I need to make sure my students are engaged! In fact, it seems like for teachers, making sense of engagement doesn’t come from trying to zoom in and dissect it, as if with a cutting tool and a microscope. Instead, we ought to zoom out like ecologists, to see engagement as part of the fabric of learning, a rich entanglement of relationships, routines, expectations, and outcomes, for individual students and entire classrooms.

Schlechty’s “Levels of Engagement"

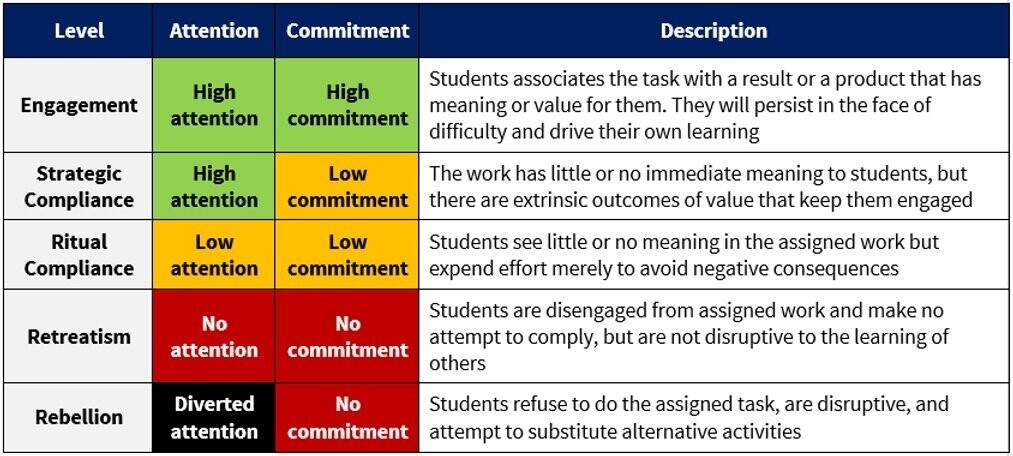

To that end, as a teacher writing for teachers, I want to introduce a more useful tool - not one for the precise modeling or measurement of student engagement, but one that provides a holistic vocabulary for talking about the quality of engagement we see in our classrooms. This tool is called Schlechty’s “Levels of Engagement.”

Eldridge, Ayrton. “How PBL Creates Authentic Student Engagement — PBL Curriculum.” Cura Education, 7 February 2022, https://www.curaeducation.com/best-practice/how-pbl-creates-authentic-student-engagement. Accessed 13 May 2022.

Eldridge, Ayrton. “How PBL Creates Authentic Student Engagement — PBL Curriculum.” Cura Education, 7 February 2022, https://www.curaeducation.com/best-practice/how-pbl-creates-authentic-student-engagement. Accessed 13 May 2022.

This model names multiple levels of student involvement with learning, by presenting engagement as a spectrum: from outright rebellion at the low end to a ‘stay quiet’ mentality in the middle (retreatism or ritual compliance) to true ‘engagement’ (high attention + high commitment) at the apex. These are all recognizable modes of student interaction in the classroom, and with learning. As teachers, we’ve all seen these behaviors, or modes of engagement, play out in our classrooms. Furthermore, by labeling the level of engagement rather than the student, we carefully use language to highlight how students may cycle through these different modes or postures in different subjects, days of the week or times of the day, over time, and/or developmentally.

What I love about Schlechty’s model is that instead of trying to objectively measure or quantify student engagement the way the researchers attempted, the model offers educators a way to talk about the quality of engagement, in an approximate way we can easily understand and use, without needing to precisely quantify our terms.

In other words, this model makes sense to me, as a teacher. I recognize these levels from my own learning journeys, and can recognize straight away that glint in the eye of students operating at that highest level of engagement, and how that is correlated with both high attention and high commitment. The other stages of engagement reap less reward for learners on much less investment. We know from experience what ‘ritual compliance’ feels like from the inside and looks like from the outside, and how that level of investment or involvement doesn’t drive long-term retention of learning.

Using Schlechty’s levels of engagement as a tool or vocabulary for discussing engagement in the classroom opens the discussion out onto the recognizable vista of teaching and learning, rather than limiting our discussion to quantifiable measures, and this reminds me of other familiar topics and voices. For instance, I’m reminded of the excellent Powerful Teaching by Pooja K. Agarwal and Patrice M. Bain - an exploration of practical applications of learning science, primarily around the use of retrieval practice, interleaving & spacing of material, and metacognitive feedback. These are techniques to engineer the “desirable difficulties” that grow lasting connections in the brain. “Decades of research have shown that fast, easy strategies lead to short-term learning, whereas slower effortful strategies lead to long-term learning.” In other words, our goal in the classroom is not how to lower the bar for expectation or rigor, rather, it’s how to elevate student engagement for greatest investment in learning - that’s where gains are earned and learning is retained! High engagement is the key to retention.

In another direction, I’m reminded of Ron Berger (of "Austin’s butterfly" fame) and his Ethic of Excellence. Berger tells how in his small school in rural Vermont he was able to guide cohorts of elementary students through challenging learning journeys in which they produced professional-grade work, whether artistic, scientific or literary. One of his primary methods for doing so was the curation, over years, of exemplars. These exemplars, and their study, meant that the efforts of past students could actually inspire those of the present. Exemplars are also rich material for pattern recognition - or, to be a bit poetic, ‘one good exemplar is worth a thousand rubrics.’ Berger details how he allowed the creative tension the exemplars inspired in students to drive their high engagement with their own work. In fact, in his books, he shares multiple anecdotes about running into former students as adults, who still marveled at their growth in his grade 6 classroom! That sounds like very high engagement indeed, and the memory and experience of that learning was clearly retained over time.

In my own work, I have found that Peer Review can drive high engagement with students in Grades 5 and 6 as well. What I call ‘Structured Peer Review’ creates a system where all students have skin-in-the-game, and when students use task-specific success criteria to evaluate the work of peers (and in turn, themselves) we see rapid advancements in clarifying misconceptions and raising the level of quality of student work. Peer Review can drive high engagement, clarify expectations, and it shifts the focus from the student to the work itself, in a standards-based way.

In Summary...

To recap: we started this exploration by talking about engagement, and how when researchers go looking for it, engagement can be difficult to understand and define - that’s the reductionist approach of zooming in and dissecting. Yet, once we picked up Schlechty’s Levels of Engagement model, engagement became illuminated as a spectrum of recognizable modes of involvement with learning. In fact, that’s when we stopped talking about the construct of "engagement" and started talking about "high attention + high commitment", desirable difficulties for learning, high expectations and exemplar study, peer review, skin-in-the-game and success criteria.

My takeaway as a teacher, for teachers, is that engagement isn’t one thing that we can pin down and study in isolation - leave that to the researchers! For teachers, engagement is one aspect of a healthy learning ecosystem, composed of relationships, routines, expectations, and practices. For teachers, the study of engagement isn’t anatomy, it’s ecology! The UDL framework provides the plans and the tools to grow engagement in our classrooms, by suggesting we provide students options for recruiting interest, sustaining effort and persistence, and self-regulation. As teachers, the job isn’t to measure engagement, but to use all the elements of effective classroom learning to drive high engagement and maximize learning. Our ultimate aim, after all, is to grow expert learning behaviors in our students!