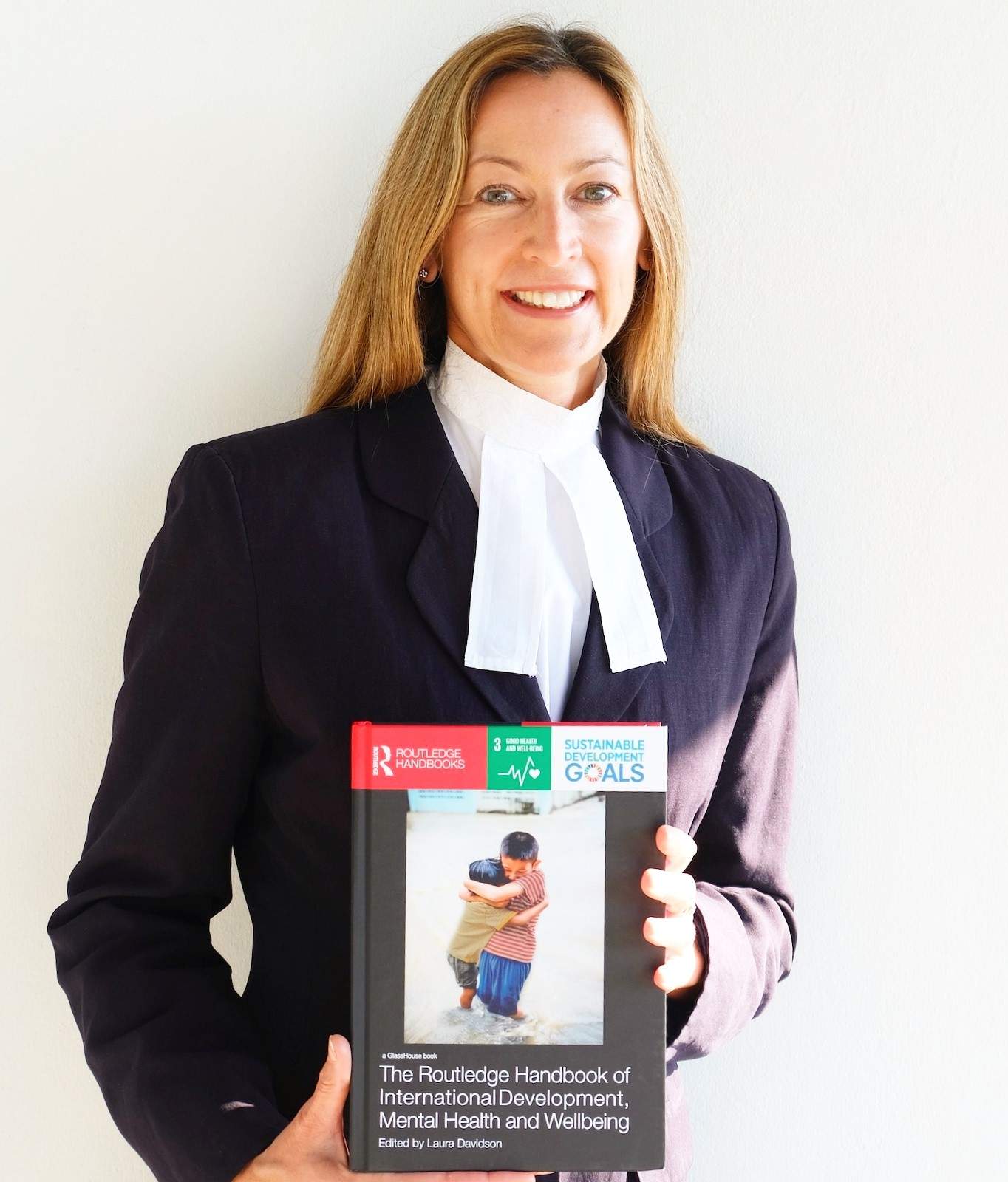

Laura Davidson is our latest Routledge Featured Author. Read our interview to discover more about her recent book, The Routledge Handbook of International Development, Mental Health and Wellbeing.

Congratulations on the publication of your book The Routledge Handbook of International Development, Mental Health and Wellbeing. What do you want your audience to take away from the book?

Thank you! The book provides differing perspectives on mental health, with sections on its legal, cultural, policy and economic aspects. A variety of demographics are examined, such as children and young people and the elderly. Gender differences, including the oft-neglected mental health of men, are also highlighted and examined. It’s a fascinating read; a book you can dip in and out of, but which ultimately shows how mental health pervades the whole and every aspect of society. In terms of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), improving mental health and preventing mental ill-health can assist states in meeting so many of the other goals. As Jeff Sachs (the Special Advisor to the UN Secretary-General on the SDGs) notes in his Foreword, the book makes very clear that a joined-up, multi-disciplinary and multifaceted approach can truly improve mental health care globally. Not only that, but investing in mental health, including in prevention and education, provides much longer term economic benefits – a fact of which governments ought to take more notice.

What inspired you to write this book?

I’m passionate about this subject because mental health has always been a low priority worldwide. In deciding to put chapters together into a book, I was keen to explore why a commitment to investing in mental health isn’t the global priority it ought to be. Nowhere in the world does mental health enjoy parity with physical health, and most governments fail to ring-fence funding for mental health within their health budgets. It’s such a false economy, as various chapters of the book make clear. I also hoped to pique the interest of postgraduate students to learn more about mental health, particularly in the international development sphere. There are so many Masters courses on international development and global public health in the UK, Europe and the US. Mental illness is a non-communicable disease (NCD), and yet global public health Masters’ courses often devote little time to it. International development courses rarely mention it. It would be wonderful if this book led to more postgraduate students becoming advocates for the rights of persons with mental disability in low and middle income countries (LMICs).

Why is your book relevant to present day?

The UN set eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000 which spanned 15 years. Those goals were largely intended to reduce poverty in LMICs. It’s abundantly clear that mental illness and poverty are intimately connected. Untreated mental ill-health increases the likelihood of poverty, and poverty can increase the likelihood of mental ill-health. However, none of the MDG related to mental health. They’ve now been superseded by 17 SDGs, and SDG3 requires states to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”. However, how that might be achieved was unclear. This book draws together global experts who set out the evidence in terms of mental health policy, legislation, prevention, treatment and support, providing practical suggestions as to what needs to be done to improve mental health, and how states might meet SDG3.

How do you think the field of mental health is evolving today?

I’m very glad to see that mental health is being spoken about more openly. The interest of younger members of the Royal family and their involvement in mental health stigma reduction campaigns, including their mental health initiative, Heads Together, and their video for the Public Health England/NHS campaign, "Every Mind Matters", has done a great deal in breaking down the stigma surrounding mental health. Nevertheless, in my view the stigma will never be completely broken down without more research into the causes of mental illness. We’re very far behind in terms of understanding the aetiology of different mental illnesses, compared to physical health problems. The study of the brain has been extremely neglected, partly due to its complexity. That’s why I founded the UK’s first mental health research charity in 2008 (Mental Health Research UK). Our charity funds Ph.D scholarships to encourage research and capacity-build within UK universities. The Wellcome Trust has also recognised this need in the last few years. I hope the government will realise the long-term importance of research in this area and pledge meaningful funding. We need more research and better evidence-based treatment – not necessarily pharmacological treatments, although certainly the current ones that exist must be improved upon: there are far too many side-effects.What are the main developments in research that you’re seeing in your subject area of expertise?

It’s clear that we simply don’t have enough human resources worldwide in terms of mental health personnel. In the UK there are long NHS waiting lists for psychological intervention, and there aren’t enough psychologists. However, in some countries there are no psychiatrists in the whole country, or only one or two in the capital city. It’s often impossible for those in LMICs to travel to the capital due to a lack of funds. Furthermore, many trained mental health clinicians leave their countries for higher salaries in the west. A key trend in LMICs, therefore, has been the training of lay personnel at the primary care level in rural areas through what is known as ‘task-shifting’ or ‘task-sharing’, in order to meet the need for mental health support. They’re also able to identify and refer more complex cases to experts at the tertiary level. There’s a growing body of research evidence that shows this innovative solution is effective. However, it’s only a short-term solution to the scarcity of trained psychiatrists and psychologists in LMICs, and every country needs to train more mental health personnel for the future.Another interesting development relates to the detention of psychiatric patients on the basis of their (mental) disability. There’s finally recognition that this is discriminatory and therefore a breach of their human rights, including under Article 1 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) which makes it clear that mental health falls within the definition of “disability”. One positive development is that there’s a trend towards de-institutionalisation, since locking people up against their wishes in a hospital full of other acutely unwell patients is unlikely to be optimal in improving mental health. Nonetheless, sometimes it’s the only option to keep someone safe from self-harm, or where the symptoms of their mental illness makes them a threat to the safety of others. In some LMICs, stigma, a lack of resources, or a lack of knowledge makes this a first resort, rather than a last one.

As a human rights Barrister, the disjunct between domestic legislation permitting psychiatric detention and the obvious discrimination of psychiatric patients on the grounds of health is a fascinating intellectual conundrum. It must also be remembered that enforced hospitalisation is a real-life issue which causes millions of people around the world real pain and trauma, and compounds stigma. How to eliminate the discrimination is a highly complex problem. It’ll be interesting to see how thinking around this develops within human rights discourse in the next few years.

Finally, the chapter by Sean Kidd and Kwami McKenzie (Chapter 6) which looks at a social entrepreneurship approach to mental illness in LMICs is, I hope, a foretaste of what’s to come. A more sustainable, social enterprise approach to solving world problems is a current trend, and I welcome seeing such innovation in the field of mental health.

How does your book relate to these recent developments?

There are numerous chapters in the book which deal with the human resource problem within mental health. For example, my own chapter co-written with Larry Gostin on the rights to mental health and development (Chapter 2) discusses the need to tackle the problem, and the innovation needed more generally in the mental health sphere. In Chapter 4, Judy Bass examines the relationship between mental health and poverty in LMICs, and she includes consideration of task-shifting. Similarly, this is touched on by Cornelius Ani and Olayinka Omigbodun in Chapter 11 which examines the SDGs and child and adolescent mental health in LMICs, with an interesting case study on Nigeria.Part V of the book is the legal section, and various contributing authors discuss the right to liberty, which is at the core of the arguments about the compulsory detention of those with mental illness. Peter Bartlett and David Bilchitz provide their own differing perspectives and critiques in Chapters 18 and 19 respectively, which makes for fascinating reading. In Chapter 15, the UN Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Dainius Pūras, critiques along with Julie Hannah (Chapter 15) the paternalistic biomedical model of mental health treatment, challenging the world to find better and more effective non-pharmacological alternatives.

What makes your book stand out from its competitors?

This is the first book which focuses on mental health in the context of international development. That’s quite hard to believe, given the number of people worldwide who suffer from mental ill-health in their lifetime. Most books on public health give scant space to mental health, and there are very few books considering it in the development context. A pertinent feature of the book is that it contains numerous chapters written by people with lived experience of mental ill-health. Despite considerable rhetoric about mental health and the need to break down stigma, few academic platforms exist which provide a voice for those most affected. This book is one of them.Is there one piece of research included in the book which surprised you or challenged your previous understanding of the topic?

I think every chapter is extremely interesting, but I found Peter Lehmann’s personal perspective as someone with lived experience of mental ill-health and compulsory detention particularly compelling and thought-provoking (Chapter 17). Joseph Calabrese’s anthropological angle and intimate knowledge of mental illness in the context of Bhutan and Native North Americans was enlightening in Chapter 7. I also found the country case study on Israel written by Sharon Primor and Dahlia Virtzberg inspiring. They explain how unlawful practices which abused the human rights of psychiatric patients were challenged and changed through grassroots activism.What did you enjoy about writing the book?

I always enjoy the analytic process of writing an academic article or book chapter, and it was no different when writing my four chapters (two of which were co-written with Shekhar Saxena and Larry Gostin respectively). Editing the other chapters was also a pleasure, given their differing yet interlinking perspectives. I know it’s my book and I’m biased, but I found every chapter both interesting and inspiring for differing reasons!

What is your academic background?

I’m a Barrister at No.5 Chambers in London and my work at the Bar is very practical, but I’ve always had a strong academic interest too. I did an LLM in international law and a Ph.D in human rights at the University of Cambridge. For the last few years, I’ve also been a visiting academic at the University of Cape Town (where much of the book was edited).

What do you think are your most significant research accomplishments?

My most interesting research so far was my qualitative empirical research in Uganda on trauma counselling services which I undertook with a clinical psychologist. After the practical fieldwork, I analysed the impact of our findings for law and policy in the region. Our research was published in a number of journals. We were recently gratified to be informed by a government official that our research had indeed influenced government policy on mental health in the country.What first attracted you to mental health as an area of study?

I had always been interested in medical law, and when I undertook my Ph.D, I had to ensure that my topic was ‘new’ and innovative. This was not long after the UK’s Human Rights Act 1998 had come into force, yet I was surprised to find that no-one seemed to be doing any legal research on the rights of persons with mental illness. Not having previously studied mental health law, I thought it would keep my attention for three years. It then became my passion and my professional area of specialisation at the Bar.

Tell us an unusual fact about yourself?

I used to be a modern pentathlete, and have many caps for my country in fencing, including representing Northern Ireland in the 2006 Commonwealth Fencing Games.

What advice would you give to an aspiring researcher in your field?

We need far more researchers in mental health – particularly scientific researchers to shed light on the mysteries of the brain so that pharmacological treatments can be improved. The world needs far more clinical psychologists, and I hope more students will enter that field. At the same time, we also require increased evidence-based research on what works in practice in terms of mental health treatment and support within different cultures, especially in LMICs.

What is the last non-academic book you read?

I love reading fiction to unwind, and the book I’m currently reading is called, The Little Coffee Shop of Kabul, by Deborah Rodriguez. The last book I read had the rather uninspiring title of The Worst Date Ever, by Jane Bussman, but it’s actually an incisively written and true story of a celebrity journalist’s foray into investigative journalism. She stumbles upon some truths about Joseph Kony and why the Lord’s Resistance Army managed to flourish for so long in Uganda. During my Ugandan research I interviewed many former child soldiers and child sex-slaves, so this was an eye-opening read for me.

Do you have plans for future books? What’s next in the pipeline for you?

I plan to continue working in mental health and disability law, and I’m keen to undertake more consultancy work in LMICs. Routledge has indicated that it would like this book to be updated in a few years’ time, so we’ll see if I have time for that!

What do you feel has been a highlight for you, in your career?

There are too many legal cases to mention which have made me feel like my hard work is worthwhile, but helping to ensure the discharge of a compulsory detained patient who has recovered from mental illness is always a highlight. When I assist clients in winning damages in recognition of a violation of their human rights, this also gives me a buzz. Sometimes hospitals and local authorities can forget that patients and their relatives are real people and decisions of such bodies can have a huge adverse impact on their lives. I hope in my work as a lawyer I can make them feel supported and understood, and that their wishes and hopes were fought for. As a development consultant, drafting Rwanda’s first mental health law and advising the government on mental health policy in 2013 was definitely very special. It’s a stunning country with a terrible and shocking history, but its resilience is evident in how far it’s come in recovering from the genocide.

What do you see yourself doing in ten years' time?

I hope more of the same – I enjoy the challenge of a mixture of court work, academic writing, and international consultancy and advisory work. I really hope that more governments will recognise the importance and value of improving their citizens’ mental health – and that I can help them with that. I’ll continue fighting to uphold the rights of those with mental disability as long as I’m able to.

The Routledge Handbook of International Development, Mental Health and Wellbeing, 1st Edition

Author(s): Laura Davidson

Price: $280.00

Cat. #: K405151

ISBN: 9780367027735

Publication Date: June 24, 2019

Binding: Hardback