Phillip Wadds

Dr Phillip Wadds is Senior Lecturer in Criminology at the UNSW, Sydney and researches across five interrelated themes: policing; crime prevention; public leisure; alcohol and other drugs; and violence. He has spent the last decade undertaking ethnographic and field-based research examining various features of nightlife and related leisure in Australia with an enduring focus on its policing, regulation and governance.

Subjects: Criminology and Criminal Justice

Biography

Dr Phillip Wadds is Senior Lecturer in Criminology and the Criminology Program Convenor at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. He researches across five interrelated themes: policing; crime prevention; public leisure; alcohol and other drugs; and violence. He has spent the last decade undertaking ethnographic and field-based research examining various features of nightlife and related leisure in Australia with an enduring focus on its policing, regulation and governance.Dr Wadds has a developing national and international profile in the fields of criminology and policing studies with his research having ongoing influence on policy and practice in the area of urban planning and governance, harm reduction, sexual violence prevention and the policing and regulation of licensed environments. He has extensive experience working with key stakeholders to improve safety outcomes in spaces of high risk for alcohol and drug-related harm. In recognition of his research expertise, Dr Wadds was appointed to both the City of Sydney Council’s Nightlife

and Creative Sector Advisory Panel and The City of Randwick’s Night-Time Economy Advisory Committee in 2018.

To date, Dr Wadds has been a Chief Investigator on internal and external grants totalling $292,401.51, as well as working as a project manager on three external grants worth $813,284. He has 26 publications, including 2 books, 8 book chapters, 7 journal articles and 7 non-traditional research outputs (including 4 research reports).

His most recent project involved world first research into issues of public safety and sexual violence at Australian music festivals. Co-led with Dr Bianca Fileborn, this project examined the specific socio-cultural, spatial and gendered dynamics of music festivals as sites of particular risk relating to sexual violence and AOD-related harm. The project received significant media and industry attention and resulted in policy change from a number of large national festival operators as well as state policing and health agencies (NSW Police and NSW Health). This project won the 2019 Australian and New Zealand Society of Criminology Adam Sutton Crime Prevention Award for its impact on policy and practice around issues of sexual violence at Australian music

festivals.

Education

-

PhD Criminology (Western Sydney University) - December 2013

Areas of Research / Professional Expertise

-

Policing, urban governance, drinking and drug use, crime prevention, and qualitative research methods.

Websites

Books

News

How music festivals can change the tune on sexual violence

By: Phillip Wadds

This year’s summer music festival season has again been marred by several incidents of sexual assault. Three incidents of sexual assault were reported at the Falls Festival at Tasmania’s Marion Bay, in a repeat of similar incidents at last year’s festival. And disturbing footage of a man groping a woman at the Rhythm and Vines Festival in New Zealand on New Year’s Eve quickly went viral.

A groundswell of activism around sexual harassment and assault at music festivals is taking place. Australian band Camp Cope’s It Takes One campaign is calling on organisers and artists to change the culture underpinning sexual violence at festivals.

Similarly, the Your Choice movement, which was launched in 2017, promotes cultural change and encourages bystander intervention at music events.

Internationally, the UK-based Safe Gigs for Women works with venues and festivals to eliminate sexual harassment and assault.

All of these developments are occurring alongside an increasing public outcry about the pervasive and systemic nature of sexual violence. But what do we actually know about sexual violence at music festivals? And what is it about these spaces (and their patrons) that facilitate acts of sexual violence?

How common is sexual violence and harassment?

Social media campaigns like #MeToo have demonstrated that sexual harassment and assault are widespread and not limited to any one social or cultural setting. Nonetheless, a string of high-profile incidents and campaigns suggests that music festivals could be a hotspot for this type of violence.

There is virtually no research on sexual violence at music festivals; we are aiming to change this with our current research project. This lack of research makes it difficult to know how prevalent sexual violence at festivals is beyond high-profile, anecdotal cases that have been picked up by the media.

However, we can draw on research on sexual violence and harassment from other settings to gain some insight into what might be happening at festivals.

Young women are consistently identified as the age group most at risk of being sexually harassed or assaulted. In Australia, women aged 18-34 are the most likely to have experienced sexual harassment in the past 12 months. Also, 38% of 18-24-year-olds and 25% of 25-34-year-olds have experienced sexual harassment in the past year.

Gender- and sexuality-diverse people also face disproportionately high rates of sexual harassment and assault.

These statistics suggest we need to look at the social and cultural locations that young people inhabit when thinking about sexual violence.

Although most sexual assault takes place in private, residential locations between people who know each other, younger people are more likely to experience sexual assault in a wider range of locations and to be assaulted by someone other than an intimate partner.

So, sexual harassment and assault are common experiences in general. There is no reason to assume this is any different at music festivals. Music festivals tend to be geared toward young audiences, and, as such, may constitute the site of sexual harassment and assault against younger women, and gender- and sexuality-diverse people.

Research in analogous settings, such as licensed venues, suggests that sexual harassment and assault are commonplace. One of the co-authors’ research on unwanted sexual attention in licensed venues in Melbourne found that young people perceived this behaviour as being pervasive and commonplace.

Further reading: Sexual violence in pubs and clubs: just a normal night out?

A Canadian study similarly reported that 75% of women in their sample had experienced unwanted sexual touching or persistence in bar-room environments.

Music festivals share many features with licensed venues that are likely to facilitate sexual violence. Large crowds of patrons, and the anonymity this provides, can enable perpetrators to sexually harass with apparent impunity.

Consumption of drugs and alcohol in these settings can also work to perpetrators’ advantage. For example, it can help downplay their own behaviour (“they were drunk and didn’t know what they were doing”), or target those who may have overindulged and become incapacitated.

Gender inequality

Australia’s music industry is male-dominated; male artists tend to dominate festival line-ups.

Gender inequality permeates the entire industry. Research shows that women (and, almost certainly, gender-diverse people) are underrepresented, undervalued and underpaid in virtually all facets of the Australian music industry.

Sexual violence is known to be more likely to occur in contexts of gender inequality. This suggests music festivals – and the Australian music industry generally – may provide a cultural context in which the preconditions for sexual and gender-based violence abound.

Changing the beat

Given all this, it’s reassuring that efforts to prevent sexual violence at festivals, and to generate broader cultural change within the industry, are taking place. However, change is slow, and pockets of resistance persist within the sector. This has led some to call for festival boycotts or to ban men from festivals.

The current campaigns feature some promising elements, particularly in their focus on bystander intervention, and encouraging influential artists and industry leaders to call out inappropriate behaviour and take a stand against sexual violence.

However, there are many other steps festival organisers could take to prevent or reduce sexual violence, and to ensure they respond appropriately when it occurs. These include:

-

introducing a policy on sexual harassment and assault that takes a zero-tolerance stance against this behaviour. This should include specifying consequences for perpetrators (like being ejected or banned from the festival, and potential legal ramifications). This should be clearly communicated to festival patrons, staff and volunteers, and consistently enforced;

-

training all festival staff, security and volunteers to identify and respond appropriately to incidents of sexual harassment and assault;

-

encouraging artists to take a stand against sexual violence, and to call out any bad behaviour they witness from the stage;

-

running high-profile prevention and bystander intervention campaigns; and

-

ensuring there are clear avenues for patrons to report incidents that occur at festivals.

Such actions need to occur alongside more widespread efforts and interventions. Ensuring all young people receive comprehensive sexuality and respectful relationships education is vital. And continued efforts to tackle the broader issue of gender inequality in the music industry are required.

We’d like to talk to people who have experienced sexual harassment or assault at an Australian music festival. You can find out more about our project here.

If you require support for sexual harassment or assault, contact details for national services are available here.

Where are they now? What public transport data reveal about lockout laws and nightlife patronage

By: Phillip Wadds

It is vital that public policy be driven by rigorous research. In the last decade key policy changes have had profound impacts on nightlife in Sydney’s inner city and suburbs. The most significant and controversial of these has been the 2014 “lockout laws”.

These were a series of legislative and regulatory policies aimed at reducing alcohol-related violence and disorder through new criminal penalties and key trading restrictions, including 1.30am lockouts and a 3am end to service in select urban “hotspots”.

A range of lobbyists, including New South Wales Police and accident and emergency services, welcomed these initiatives.

By contrast, venue operators, industry organisations and patron groups have made repeated but largely anecdotal claims that these changes caused a sharp downturn in profit, employment and cultural vibrancy in targeted areas. They also claim that the “lockouts” have caused drinking-related problems to spill over into urban areas that are less equipped to cope with them.

Crime is down

However, in late 2016, the Callinan Review referenced compelling evidence in support of the current policy.

According to the latest research, recorded rates of crime are down by around 49% in the designated Kings Cross precinct and 13% in Sydney’s CBD.

In contrast, what little research has been produced by opponents of strict nightlife regulation has been criticised as unreliable, inaccurate and poorly deployed.

The Callinan Review noted the lack of verifiable claims about the negative impacts of the policy in submissions from the main opponents of the lockout laws. This has led to a great deal of assumption in the final report about where, for example, revellers, jobs, entertainment and revenue might have been displaced to, or how the policy changes affected them.

In many respects, the passing over of claims made by anti-lockout groups is rather unfair. These groups are not official state bodies with the capacity to produce the type of data or evidence on which the policy has been justified and defended. As such, their “unscientific” observations and experiences have been largely dismissed.

To critically balance and juxtapose opposing claims, more impact data and research are needed.

We must take a city-wide perspective

If the lockout policy is judged on the original goal of decreasing crime in designated “hotspots”, then it appears to have been a success.

However, from a city-wide perspective there are other issues to consider. Not the least of these is the effects in other nightlife sites across Sydney.

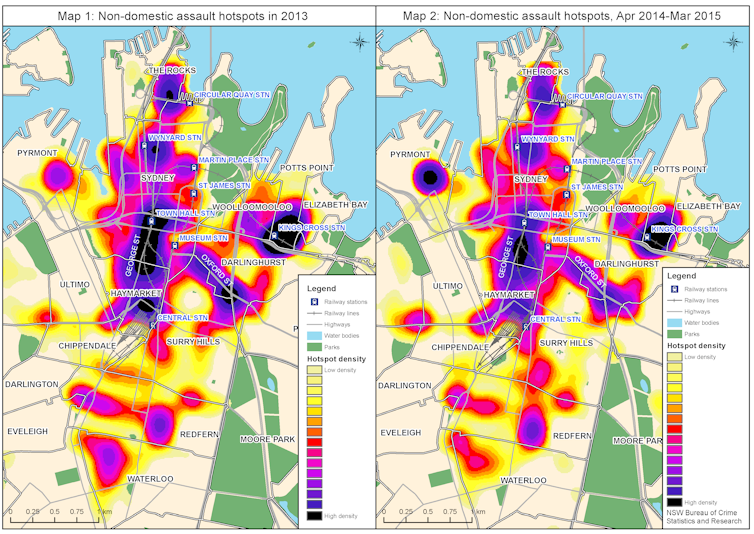

Despite initially finding no displacement of violence to nearby nightlife sites, the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) has just released findings showing significant displacement in rates of recorded non-domestic-related violence in destinations outside the lockout zone.

Reported crime rates in Newtown, one of the displacement sites listed in the BOCSAR study (along with Bondi and Double Bay), increased by 17% in the 32 months following the lockouts.

These new findings appear to vindicate some local complaints about increased night violence – including attacks targeting LGBTI victims – that has led to much resident irritation and even political protest in recent years.

Adjusting our nightlife habits

So, how can we better judge the veracity of these claims about the displacement of nuisance and violence?

Mapping patronage trends is a key means of understanding how and why rates of assault have now increased despite initially showing little to no change.

To this end, Kevin McIsaac and I, with data from Transport for NSW, have set out to ascertain if and how nightlife participation in Sydney has been influenced by the lockouts.

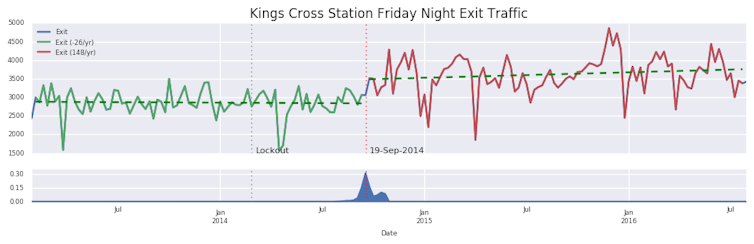

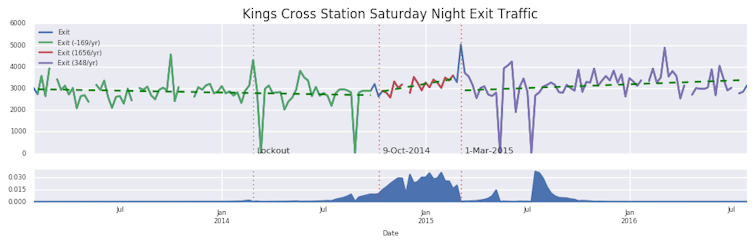

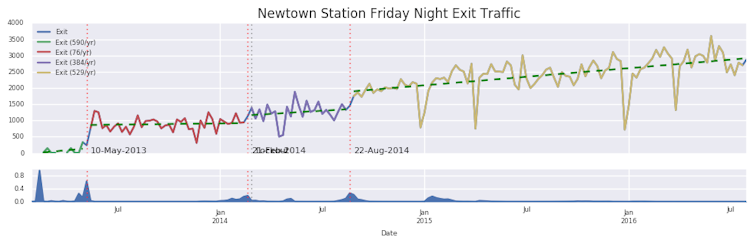

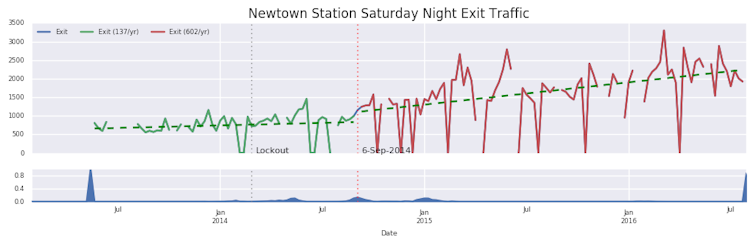

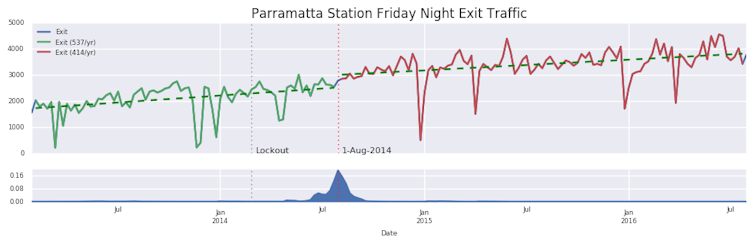

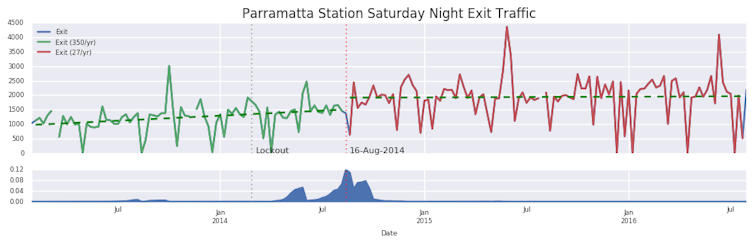

Our analysis focused on night-time aggregated train validation data (turnstile counts) from January 2013 to July 2016 for stations servicing the designated nightlife precincts (Kings Cross, Town Hall) and precincts outside the lock-out zone (Newtown, Parramatta).

Using Bayesian Change Point (BCP) detection we found the following:

-

no evidence of changes to Kings Cross or Parramatta exit traffic from the introduction of the lockout laws;

-

evidence of strong growth in the Parramatta Friday-night exit traffic by about 200% since January 2013, which is independent of the lockout laws;

-

evidence of an increase of about 300% in the Newtown Friday-night exit traffic as a result of the lock-out laws; and

-

in all stations, the BCP algorithm detected a change when OPAL card usage exceeded magnetic ticket usage. This suggests the jumps seen in the graphs below are due to the higher exit reporting from OPAL. The switch from flat to slow growth in trend is probably an artefact of the relative increase in OPAL usage.

These findings provide new insights into the way people have adjusted their nightlife habits. The most interesting finding is the dramatic increase in access to Newtown nightlife. Exits in Newtown have increased 300% since the lock-outs were introduced in 2014.

As can be seen from the graph, the rate of increase has been steady over the study period. This raises questions about whether there is a threshold at which patron density becomes an issue that potentially results in increased nuisance and violence.

Big data’s capacity to help

While this research is still in its early phases, the transport data tell one small, yet significant, part of the story. However, to draw definite conclusions, there is far more that needs to be considered.

Many nightlife patrons travel into the city by different means, or don’t travel at all (those who live in and around the city).

We need alternative data to try to identify patterns concerning these groups. Several different organisations have data that could help paint a more complete picture, including telcos, Google, Taxis NSW and Uber.

While these organisations should be protective of their data, the value of anonymous aggregate location data is how it can inform and advance public policy through ethical research. This information is key to breaking down access barriers. Without access to these anonymous aggregations of privately controlled data, the capacity of research is limited.

As such, there is a need for greater communication, collaboration and co-operation between producers of big data, the government and researchers into social impact. By building stronger evidence for all manner of policies, such partnerships have an amazing potential to contribute to the public good.

New research shines light on sexual violence at Australian music festivals

By: Phillip Wadds

As the weather warms up, it can only mean one thing for young music enthusiasts: the Australian summer music festival season is here. For many young people, this is a time of great anticipation, excitement and meticulous planning of outfits.

Unfortunately, it also raises the issue of sexual violence that has blighted festivals in recent years.

This issue has attracted increased public agitation and attention, as illustrated through media reporting, activism, and the gradual introduction of festival policies and prevention efforts.

Despite this, there has been virtually no research on sexual violence at music festivals. This is surprising, given that they bring together a range of factors that are associated with a heightened risk of sexual violence, such as high levels of drug and alcohol consumption.

Read more: How music festivals can change the tune on sexual violence

As one international exception, a recent survey by YouGov shed some initial light on the issue, with findings indicating that two in five young women (and approximately one in five young men) had experienced sexual harassment at festivals in the UK.

But beyond this study, there is very little documented evidence about sexual violence at music festivals, and none within Australia.

To address this gap, my colleagues and I conducted the first study into perceptions and experiences of sexual violence at Australian music festivals. We focused on forms of sexual violence ranging from sexual harassment (such as wolf-whistling and unwanted verbal comments) through to behaviours that might meet legal thresholds for sexual assault.

We conducted an online survey of 500 people who attend Australian music festivals on their perceptions of safety and sexual violence at festivals.

We also spoke to 16 individuals who had either experienced sexual violence, or been involved in responding to an incident, at music festivals across the country.

General perceptions of safety

Most of our participants felt safe most of the time at Australian music festivals, with 61.5% saying that they “usually” felt safe, and 29% responding that they “always” feel safe at festivals.

This is an important finding, as it cautions us to resist viewing festivals as inherently risky or dangerous spaces, and to avoid perpetuating the moral panic that often accompanies youth leisure practices.

Men more consistently said they felt safe compared to women and LGBT participants. For example, men were equally as likely to say they either “always” (47%) or “usually” (46%) felt safe, with 3% of men saying they “sometimes” felt safe. In comparison, 20.4% of women said they “always” felt safe, 68.8% “usually” felt safe, and 8.4% reported that they only “sometimes” felt safe. This finding resonates with previous research on gender, sexuality and safety across a range of contexts.

The presence of friends was the most significant factor influencing parcipants’ sense of safety. However, this is a double-edged sword when it comes to sexual violence, given that we are most at risk of perpetration from someone we know.

Conversely, other patrons’ drug and alcohol consumption and overcrowding were the factors participants most commonly associated with feeling “unsafe” at a festival.

Perceptions of sexual violence

An overwhelming majority of participants thought that sexual harassment (87.5%) and sexual assault (74.1%) occurred at music festivals. Certainly, this perception is consistent with the emerging international and anecdotal evidence.

Sexual harassment was perceived to be a common occurrence at festivals. The majority of participants believed it happened “often” (31.2%) or “very often” (30.2%). In contrast, participants believed sexual assault was less common, with the majority of participants saying that it happens “sometimes” (33%) or “not very often” (26.5%).

Participants recognised the gendered nature of these experiences, with women seen as most likely to experience sexual harassment (86.7%) and sexual assault (86%).

Experiences of sexual violence

Experiences shared by interview participants spanned a range of “types” of sexual violence, from harassing behaviours such as verbal comments, through to acts that would likely meet legal thresholds for sexual assault.

Sexual harassment was particularly common, in line with survey participants’ perspectives. Notably, most of our participants had multiple experiences of sexual violence, and/or knew friends who had similar experiences.

Interview participants’ experiences further illustrated how the environmental and contextual features of festivals could be used to facilitate and excuse perpetration.

Crowded spaces such as the mosh pit were most frequently identified as sites of sexual violence. For example, perpetrators were able to use the packed nature of these spaces to create a level of ambiguity about, or “get away with”, their behaviour. In such settings, it was often difficult for participants to know if an incident was intentional, or just the unfortunate result of a crowded, often physically aggressive space.

In less ambiguous situations, perpetrators could easily disappear into the crowd, making it difficult to do anything about the incident.

Read more: Rape, sexual assault and sexual harassment: what’s the difference?

Such experiences can and do profoundly impact women’s ability to fully participate in music festivals. Participants often said they changed the way they dressed, were less likely to inhabit crowded spaces (such as the mosh), and were often hyper-vigilant.

In short, sexual violence reduced the ability of women to enjoy these important social and cultural events, in addition to the well documented impacts of sexual violence.

So now we know, what next?

Our research provides some important initial insights into the issue of sexual violence at music festivals. It supports what the mounting anecdotal evidence has suggested: that sexual violence in various forms is a significant issue at music festivals.

Of course, it is important to remember that sexual violence occurs across many spaces. In fact, it is most likely to occur in private residential areas. So, it is vital not to demonise festivals as particularly problematic spaces.

Nonetheless, in order to prevent sexual violence, we must address it wherever it occurs. It is heartening that many festivals in Australia and internationally have begun to implement policies to tackle this behaviour.

Our research highlights the importance of these developments, and the need to ensure such responses are implemented and evaluated consistently across festivals.

Our findings also point to the need for responses that are tailored to the unique dynamics of music festivals. A “one-size-fits-all” approach is unlikely to be effective.

If we take these steps, we can start to change the tune of sexual violence at festivals.

'THEY DON’T WANT TO DO THIS': SUMMER FESTIVAL SEASON UNDER THREAT IN NSW

By: Phillip Wadds

The reintroduction of controversial licensing legislation could see major NSW music festivals ditch the state for greener pastures.

Major music festivals have threatened to leave New South Wales in reaction to Premier Gladys Berejiklian reintroducing controversial licensing legislation to parliament.

The Australian Festival Association, which represents festivals like Splendour In The Grass, Falls Festival, Laneway, Groovin’ The Moo and more, today released a joint statement saying that they’ve been left with no other choice but to “consider their options.”

The suggested legislation would force festivals deemed ‘high risk’ by the government to submit a safety management plan.

They would also have to foot the bill for increased onsite security and emergency services.

The legislation was first introduced in March 2019 but was thrown out in late September after it was to put a vote in the NSW upper house. It was reintroduced by Premier Berejiklian during last Wednesday’s question time.

MusicNSW Managing Director Emily Collins fears that the reintroduction of the legislation could further harm the already hurting festival industry.

“It will be a huge loss for music fans, musicians, regional communities and NSW in general if we start losing music festivals to other more welcoming states,” Collins told The Feed.

NSW’s music industry has taken enough hits in the last few years.

Festival representatives have claimed that the last minute increased costs contributed to the cancellation of Mountain Sounds festival and Psyfari earlier in the year.

UNSW Criminology lecturer Phillip Wadds has been instrumental in research concerning the festival and nightlife industry in New South Wales.

“There’s already a precedent that these restrictions may lead to some festivals not being able to run in New South Wales,” Wadds told The Feed.

The festivals don’t want to do this but there’s a certain point where it becomes untenable to run an event.

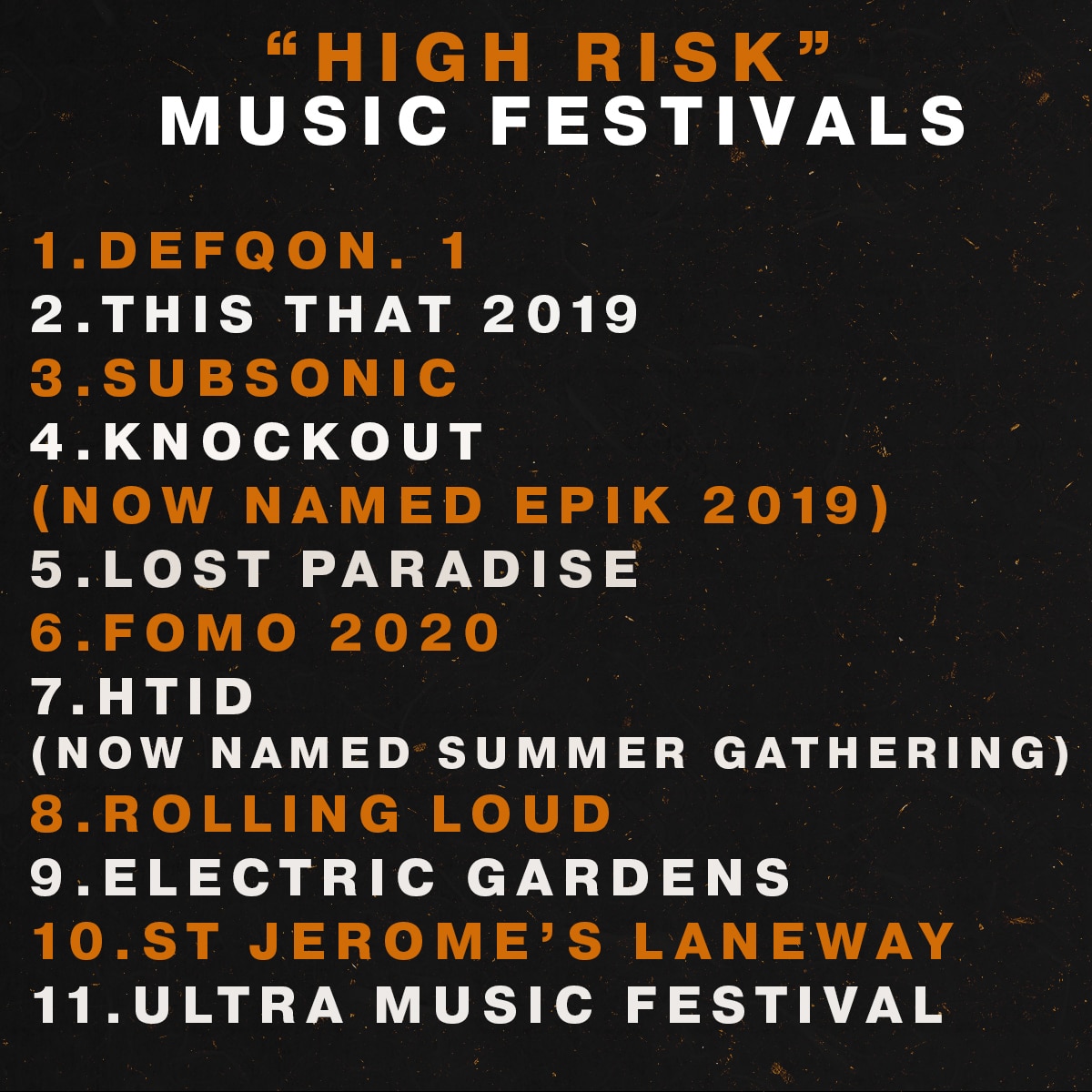

Berejiklian has said that only 11 festivals have been placed in the “high risk” category.

It’s a reduction of the original list of 14 released earlier in the year.

Much of the criticism of the legislation stems from the government's refusal to include festival bodies in the development of regulations.

“No one is asking not to be regulated, only that industry get the opportunity to assist the government with making more effective legislation,” Emily Collins said.

“We feel a legislated industry roundtable is a pretty reasonable request”

Wadds is quick to point out that the most successful policy is collaborative.

“We know that the best policy is co-produced by those it’s going to affect - it leads to better uptake and better compliance,” Wadds says.

The evidence is there that you cannot do it one-sided and without consultation with those who are going to be affected by the policy.

Berejiklian has stressed how important it was to pass the regulations before summer festival season begins.

However, Wadds believes that, if rushed into law, the legislation could put a dangerous amount of stress onto festivals.

“These are huge events with so many different moving parts so to have these last minute changes made and then to expect that an event could be compliant or face significant sanctions is not acceptable,” Wadds says.

Part of the problem is that the government doesn't understand the complexity of these events.

The move to reintroduce the licensing scheme came days after The Daily Telegraph released 40 draft recommendations from the coroner's report on festival safety.

One of the recommendations was to introduce pill testing to reduce harm at festivals.

In response, Berejiklian doubled down on her party’s stance on pill testing - commenting, “We think [pill testing] creates a false sense of security.”

Wadds impresses that the government is not seeing the bigger picture.

“We should be focusing on the health and safety of people at festivals but instead we’re focusing on government wide policy that’s distracting festival promoters from implementing more localised preventative measures,” he says.

“If we’re not focusing on event-level safety then unfortunately we’re going to see more harm in those settings.”

Why music festivals need a cultural change to combat sexual violence

By: Phillip Wadds

The Safety, Sexual Harassment and Assault at Australian Music Festivals report is the first national study to investigate sexual violence at music festivals.

Music festivals have unique settings that make them more conducive to sexual violence, says world-first research involving UNSW.

The Safety, Sexual Harassment and Assault at Australian Music Festivals report is the first Australian – and one of the only international studies – to investigate sexual violence at music festivals. The University of Melbourne and Western Sydney University contributed to the report.

“Music festivals have a unique combination of spatial, social and cultural features that make them more conducive to sexual violence,” UNSW Senior Lecturer in Criminology, Dr Phillip Wadds said. “For one, many are made up of predominantly young people who we know are far more likely to experience sexual violence across greater society. They are also often in large sprawling spaces with large crowds, but limited surveillance, particularly at night, and these elements can combine to create opportunities for perpetrators. Layered into this are high levels of intoxication, a generally masculine culture of transgression and carnival that again can encourage (largely) men to engage in harassing or assaultive behaviour.”

The report comes as a NSW coronial inquest is looking at the drug-related deaths of six people at music festivals between December 2017 and January 2019.

The research involved a survey of 500 patrons of the 2017/18 Falls Festival, on-site observations, and interviews with victim-survivors of sexual violence at any Australian festival. The vast majority (61.5%) of survey participants said they usually felt safe at music festivals, but a strong majority also indicated that they believed physical violence (92.8%), sexual harassment (95.1%) and sexual assault (88.6%) occured at music festivals.

“While survey participants indicated that they would be extremely likely to report sexual assault (75.2%) and sexual harassment (62%), this did not reflect the actions of participants who had directly experienced these forms of violence,” Dr Wadds said. “Most participants did not report to police, security or festival staff. Those who did report typically recalled negative responses from authority figures, such as victim blaming, not taking the report seriously, and/or a failure to take appropriate action.”

The research found that almost all participants (99%) consumed alcohol at music festivals, with most at ‘high-risk’ levels. Just under half of the participants (47.8%) consumed drugs. This high-level consumption of alcohol and other drugs was reported by victim-survivors of sexual violence to be a key feature of their experiences, with many perpetrators using their own intoxication to excuse their behaviour. Victims intoxication was also cited as a reason why they didn’t report.

“Unfortunately, many of the victim-survivors we spoke to said they were often taken less seriously by friends, security or police if they were intoxicated when reporting an experience of sexual violence,” Dr Wadds said. “In fact, many didn’t report at all because they felt partially responsible for their own victimisation, or didn’t want to ‘get in trouble’ from a police force which takes a hard line against drugs at festivals.”

Dr Phillip Wadds. Photo: Supplied.

Participants highlighted the mosh-pit and other crowded spaces as some of the key sites where they had been groped or received unwanted sexual attention. Perpetrators of sexual violence were overwhelmingly men, victims were mainly women, and bystanders rarely intervened when sexual violence was occurring.

“It’s often really difficult to differentiate between consensual or non-consensual sexual interaction in settings where there are lots of people hooking up,” Dr Wadds said. “Places like the mosh pit also feature lots of incidental physical contact, and so that can often be used as an excuse when someone experiences unwanted sexual contact. People were generally wary of intervening in situations because they weren’t sure how their intervention might play out. There can be high costs if they get it wrong, so a lot of people said they would only intervene in the most obvious of cases.”

The research provides a series of recommendations to combat sexual violence at festival events. “Addressing sexual violence at festivals requires all parties to be part of the solution and so we have recommended a series of practical steps that festivals, service providers and patrons can take to try and address some of the issues that emerged from our research,” Dr Wadds said. “Firstly, festival organisers and promoters need to set really clear and consistent standards of behaviour for their events, and they need to back these up. If people sexually harass or assault others, patrons need to know that there will be serious consequences, and victims need to know that their reports will be taken seriously and dealt with, with appropriate sensitivity.”

Staff and security training in appropriate ways to deal with reports of sexual harassment and assault was also recommended, alongside improvements to levels of surveillance, signage, lighting and greater access to safe spaces and counselling services.

Dr Wadds said patrons also needed to actively be part of the solution. “At the end of the day, everyone working at and attending a festival needs to be part of producing an environment that is safer. We need to build an ethic of care into festivals and start to break down the more problematic aspects of culture that facilitate, excuse or actively promote sexual violence. A lot of this responsibility falls to men in the space, as the primary perpetrators of this violence.”

The researchers have recommended further nationwide research across a broader spectrum of festival types. “We are planning the next phase of this project now which will hopefully build a more complete national picture of the diverse experiences people are having at festivals and help us improve the evidence base on which good policy can be developed.”

For more on the findings and recommendations, read the report.

UNSW academics say government response to Ice inquiry ‘disappointing’

By: Phillip Wadds

The NSW government has already ruled out five recommendations from the Ice inquiry, including pill testing and more medically-supervised injecting centres.

The NSW Government has missed an opportunity to reform the state’s response to drugs based on evidence, says the Director of the Drug Policy Modelling Program (DPMP) at UNSW Sydney’s Social Policy Research Centre.

Professor Alison Ritter AO submitted evidence to the Special Commission of Inquiry into the drug ‘Ice’ in relation to treatment services, harm reduction and drug laws.

The Inquiry’s findings and 109 recommendations were released yesterday.

Professor Ritter says it is disappointing that the government’s interim response to the Inquiry has already ruled out five recommendations.

“This has been a thorough, comprehensive review incorporating a range of expertise including from people with lived experience, clinicians, communities and academics,” Professor Ritter says.

“The 109 recommendations that the Commissioner has provided to the NSW Government provide the basis for NSW to be at the forefront of responding to drugs and reducing drug-related harm in NSW. It is very disappointing that the Government has already ruled out five of those recommendations.”

The Inquiry was established in November 2018 to investigate the nature, prevalence and impact of crystal methamphetamine (ice) and other illicit amphetamine type stimulants, including MDMA (ecstasy) in NSW.

The Inquiry heard submissions in public and private hearings in Sydney, Broken Hill, Dubbo, Lismore, Nowra and the Hunter Region.

NSW Health Minister Brad Hazzard says while 109 recommendations are being considered by the NSW government, five recommendations will not be supported.

These include additional medically-supervised injecting centres, stopping the use of drug detection dogs, placing needle and syringe programs in correctional centres and limiting police strip search powers so as not to focus on mere drug possession.

Professor Ritter says she hopes the remaining 104 recommendations will form the basis for drug policy in NSW.

“Of note, the Inquiry reported on the lack of treatment services, the high stigma experienced by people who have problems with drugs, and the lack of coordinated, planned treatment funding. As a health condition, criminal sanctions against people who use drugs are not an effective response. Resources would be better spent providing treatment services.”

Strip searches to continue

The Inquiry drew on evidence and recommendations by UNSW Law researchers, Dr Michael Grewcock and Dr Vicki Sentas in their August 2019 report Rethinking strip searches by NSW Police.

The UNSW report evidences that few charges are laid after a strip search, and the vast majority of charges for strip searches are for drug possession, not drug supply.

“While saying it supports amendments to clarify its strip search powers as required, the NSW Police Force seems committed to continuing with its current practices,” Dr Grewcock says.

“This includes humiliating and abusive practices such as forcing a naked person to squat and cough, conducting strip searches without reasonable suspicion that a person has, or is about to supply a prohibited drug, and not applying a meaningful test for what is serious and urgent.”

Dr Sentas says as the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission Inquiry revealed earlier this month, the NSW Police operating guidelines are an insufficient check on the excessive use of police power.

“The vast majority of strip searches yield either nothing or small quantities of drugs for personal use,” Dr Sentas says.

“The law needs to be amended to restrict strip searching to situations where there is a genuine, rather than a speculative risk to personal safety.”

Dr Sentas says it was disappointing that “the government has chosen short-term politics rather than the long-term benefits of a harm reduction approach to drug use and the criminal justice system”.

“Decriminalising possession and removing drug dog operations would better focus policing on investigative strategies that do disrupt drug supply.”

‘A missed opportunity’

UNSW Criminology Lecturer and social researcher Dr George (Kev) Dertadian has called for a second safe injecting facility in Western Sydney.

He says the NSW Government's decision to not consider the Inquiry's recommendation for expanding medically-supervised injecting sites in Sydney is a major blow to the prospects of meaningfully addressing the harms experienced by people who inject drugs in NSW.

“Safe injecting rooms are well evidenced and they save lives,” Dr Dertadian says. “People who inject methamphetamine in the outer suburbs of Sydney will continue to have limited access to a safe place to inject and less access to trained staff who could refer them to treatment services. Given that more safe injecting sites has the potential to address growing concern about methamphetamine as well as the emerging opioid crisis, this is clearly a missed opportunity.”

‘Real lack of consideration’

Senior Criminology lecturer Dr Phillip Wadds says the NSW Premier and the government were once again taking a hard-line stance on drug-detection dogs and substance checking, in spite of evidence and calls for change from multiple inquiries.

“It has become very evident that this government will only listen to experts and evidence when findings align with its own interests and agendas,” Dr Wadds says. “There is a real lack of consideration as to the impact that their stance will have in relation to community trust, particularly among young and marginalised people who are consistently targeted in many of the more aggressive aspects of this Government’s approach.”

Dr Wadds says that the increasing use of strip-search powers and heavy use of drug-detection dogs at music festivals was a perfect example of this approach.

“We know the direct harms that can come from those strategies, we have heard about them in many of the inquiries held last year,” Dr Wadds says. “The outcomes can be tragic. But we don’t often think about the other issues related to the policing of these spaces – like that patrons are often scared to approach the police for help because of a fear they will be questioned or punished if they are intoxicated by alcohol or other drugs.”

This was particularly the case in UNSW research into sexual violence at music festivals, which found that policing approaches deployed at festival events were a direct barrier to reporting, Dr Wadds said.

Report on sexual violence at music festivals wins crime prevention award

By: Phillip Wadds

ANZSOC’s Adam Sutton Award for 2019 recognises the impact of the Safety, Sexual Harassment and Assault at Australian Music Festivals project.

Dr Phillip Wadds, from UNSW Arts & Social Sciences, has received the Australian and New Zealand Society of Criminology’s (ANZSOC) Adam Sutton Crime Prevention Award along with his two report co-authors. The award is given each year to the crime prevention publication or project that best demonstrates pragmatic, workable solutions to Australasian crime problems, and reflects the values of a tolerant and inclusive society.

In July, the UNSW Criminology senior lecturer released the Safety, Sexual Harassment and Assault at Australian Music Festivals report with co-authors Dr Bianca Fileborn (University of Melbourne) and Professor Stephen Tomsen (Western Sydney University). It is the first Australian – and one of the few international studies – to investigate sexual violence at music festivals.

According to the award selection committee, the researchers “provided a thorough and concrete list of prevention strategies that will be of practical interested to government and non-government stakeholders”. They also described the report as “an excellent example of community-level research with a crime prevention focus”.

“The award is great, but what I am most happy about is the traction our research has received with those who are in a position to make festivals safer,” Dr Wadds said. “We have developed really productive relationships with the music festival sector, including major festival promoters, and have presented our research to key police and health agencies. Most excitingly, our research recommendations have been implemented into key policy documents designed to reduce harm at music festivals.”

The research included a survey of 500 patrons of the 2017/18 Falls Festival, on-site observations, and interviews with victim-survivors of sexual violence at any Australian festival. The project found that while more than half (61.5%) of the participants said they usually felt safe at music festivals, a majority also said they believed physical violence (92.8%), sexual harassment (95.1%) and sexual assault (88.6%) occurred.

Dr Wadds said, “Our findings highlight the complexity of festival settings. They are, on the one hand, really exciting and fun spaces where people are generally having a good time, but are also spaces where the harms experienced can be really significant and have ongoing impacts on the lives of those who are affected.”

Standards of behaviour

The report provided recommendations to combat sexual violence at festival events – including a series of practical steps for organisers, service providers and patrons that emerged from the research.

“Firstly, festival organisers and promoters need to set really clear and consistent standards of behaviour for their events, and they need to back them up with action if and when an incident occurs,” Dr Wadds said. “If people sexually harass or assault others, patrons need to know there will be serious consequences, and victims need to know their reports will be taken seriously and managed with appropriate sensitivity.”

Secondly, the report recommended training for festival and security staff in appropriate ways to deal with reports of sexual harassment and assault. This should be accompanied with improvements to surveillance, signage, lighting and better access to safe spaces and counselling services.

Patrons themselves also need to be part of the solution.

“Everyone working at and attending a festival needs to be part of producing an environment that is safer,” Dr Wadds said. “We need to build an ethic of care into festivals and start to break down the more problematic aspects of culture that facilitate, excuse or actively promote sexual violence. As the primary perpetrators of violence at festivals, a lot of this responsibility falls to men in this space.”

The report also recommended further nationwide research across a broader spectrum of festivals. “Hopefully the next phase of this project will build a more complete national picture of the diverse experiences people are having at festivals,” Dr Wadds said. “This will help us improve the evidence base to develop good policy.”