What's The Real Meaning of Pride and Why do LGBTQ+ Events Matter?

Posted on: April 24, 2023

Here Matthew D. Skinta, author of Contextual Behavior Therapy for Sexual and Gender Minority Clients, explains the importance of participating in Pride events as a communal response to celebrate identity as well as protest the injustices still faced today.

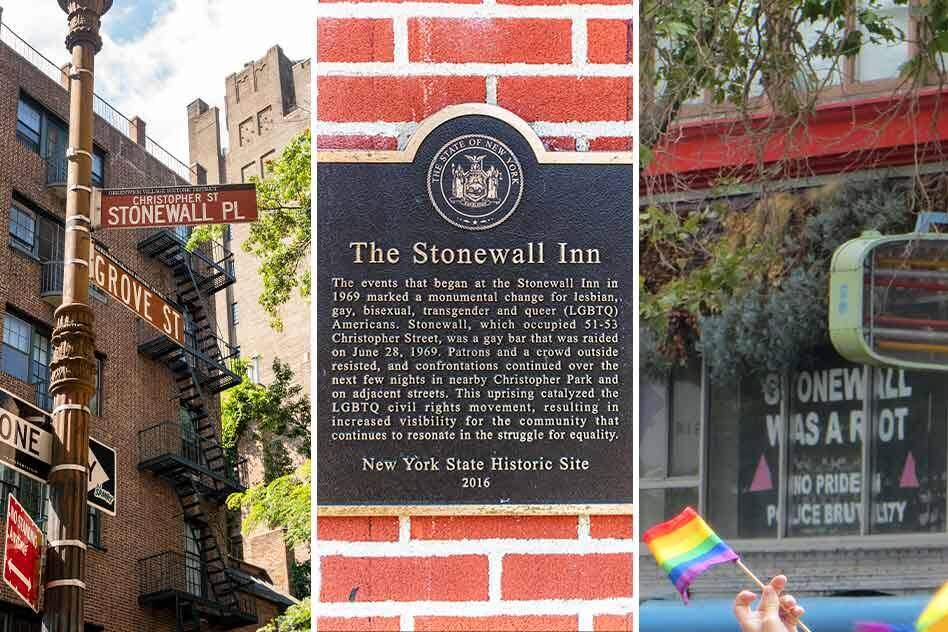

This time of year means a lot to me, and like many in the community, I recall the nervous excitement that led up to my first ever chance to share public space with other members of LGBTQ+ communities. Pride events generally cluster around June 28th, the anniversary of the Stonewall Protest when patrons of the Stonewall Inn fought back against a police raid. As a bar whose patrons included trans women, sex workers, and many queer and trans people of color, there was no expectation that politicians would seize the initiative to end these unjust raids – so members of the community took it into their own hands. Queer and trans people around the world took inspiration from this act of fighting back and claiming a visible place in public. It may be difficult now in more liberal societies to recall the context of early Pride events, when being open about one’s sexual orientation or gender identity might mean being fired from a job, losing a lease, or being shunned by one’s family.

I attended a talk in the late 1990s by psychologist Kenneth D. George, where he recounted tearing up and quickly eating his driver’s license when the police began raiding a Chicago gay bar in his youth. Being arrested and identified would have lost him his place in a doctoral program in psychology. In fact, despite the APA voting to declassify homosexuality as a mental illness in 1973, case studies on “treating” homosexuality were published in top journals into the early 1980s. Participating in Pride is more than an acknowledgement of our own belonging in the public sphere, it is a communal response to the idea that our lives should be hidden, fearful, and lived in shame.

Pride events as acts of protest

Pride events are still acts of protest used to call attention to injustices those of us in the LGBTQ+ community face. In the United States, dozens of states have recently proposed, considered, or passed laws intended to prohibit the inclusion of trans youth in sports, and some laws have been written to target or prohibit supportive and affirming medical or psychological care for trans youth and their families.

Pride events are sites of protest against corporate pinkwashing, the corporate practices of funding highly visible parade floats or LGBTQ+ friendly ads during June, despite simultaneous political donations or corporate policies that promote anti-LGBTQ+ bias. The BLM protests of 2020 have broadened discussions across the community about the meaning of a police presence at Pride events, the effect of a police presence on queer and trans people of color, and the challenges of creating a space that welcomes all bodies, genders, and expressions of sexuality.

According to the Freedom for All Americans campaign, 29 states lack comprehensive laws to protect LGBTQ+ people from employment discrimination, and despite the Supreme Court ruling in Bostock v Clayton County, Georgia that ruled that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act prohibits employment discrimination against LGBTQ+ people, similar protections in housing and public accommodations do not exist. Even in states where strong non-discrimination measures do exist, discrimination can be difficult to prove and employers still might ignore complaints of hostility. In my own career, I have worked in very liberal states with strong local and employer anti-discrimination policies, yet have still witnessed colleagues propose adopting “consciousness” clauses (i.e., a rule that would allow those training as future psychologists to discriminate against and decline to work with LGBTQ+ people).

Reducing bias among cisgender people

In the European Union, cities and villages across large sections of Poland have declared themselves LGBT-free zones. Hungary recently passed a law prohibiting inclusive LGBTQ+ materials for children and young people under the shallow guise of “protecting” youth. While there is no reason to believe that an awareness of sexual orientation and gender diversity in the world is harmful to children, a climate of shame and criminalization sends a strong message to those children who are realizing they may be trans, non-binary, gay or bisexual that they are unwanted in society.

The last pre-pandemic Pride I attended was in Budapest. Like so many parts of the world, progress and visibility are accompanied by an awareness of real risks and the possibility of being a target of violence. A Hungarian friend walking with me, behind shades and a hat to reduce the odds of being recognized by employers if photographed, was quick to point out plainclothes security heavily monitoring the march in case of violence toward those attending. Not only was the police presence strong, I noticed that those attending an official Pride Party afterward on the north part of the city had scrubbed away make-up and glitter, or had changed into more muted clothing since the march. Legislative efforts suggesting that LGBTQ+ people and visibility are a threat to children hold the possibility of raising risks of violence or discrimination, yet sharing our stories is one of the only ways that these messages might be challenged. One landmark study found that conversations that encourage taking the perspective of a trans person durably reduced bias among cisgender people. Continuing to make our experiences visible and heard through Pride events are an important step in the direction of acceptance.

Take a look inside Skinta's book, read the intro and opening chapter 'A Contextual Behavioral Analysis of Minority Stress.'

Living in an authentic and genuine way

Sharing our lived experiences is also a process that has revolutionized psychology and psychotherapy. As noted above, historically there have been a number of barriers to living openly for LGBTQ+ trainees in psychology. Compared to the era prior to the depathologization of homosexuality in the DSM, there has been an exponential increase in the number of LGBTQ+ psychologists who have been able to be their whole selves throughout their training as clinicians and researchers. Having a place at the table to show up authentically has changed the questions being asked in the field, as well as the relevance of work being done. I look back in awe at pioneers in more challenging times, like Magnus Hirschfeld in the 1890’s who saw that any meaningful science of sexual orientation and gender diversity was intrinsically political and linked to human rights work; Henry Stack Sullivan, who pioneered milieu therapy with a team of gay providers in the 1920s; or Virginia Rae Brooks, who elaborated sexual minority stress theory in 1981, and whose ideas form the central core of contemporary LGBTQ+ psychology. Pride events, from marches and speeches to museum exhibits and film festivals, provide us space to reflect on where we’ve been as a community and where we are going. We need visibility, we need community, and ultimately, we need a sense of ourselves in the flow of time as a part of an enduring movement toward living our lives in an authentic and genuine way.